Doctoral research (including PhD)

Doctoral research (including PhD)

Postgraduate research at doctoral level is different from undergraduate and taught Master’s level degree study because it involves creating new knowledge or applying existing knowledge in a new way – making ‘an original contribution to knowledge’.

In the UK, the amount of taught study in a doctorate is very limited – it is a degree programme mostly ‘by research’. Many current doctoral programmes involve doing a distinct piece of scientific research (see below), likely to be linked to the work of a senior scientist or research lab/department, but also training in research methods and wider skills (although the latter may be through a variety of development opportunities rather than ‘taught’). In all cases a doctorate will be mentored by one or more academic supervisors.

To gain a doctoral degree such as a PhD it is necessary to:

-

Acquire and understand a substantial body of knowledge at the forefront of the discipline or area of professional practice.

-

Conceptualise, design, and implement a project to generate new knowledge or understanding.

-

Write a thesis which will be examined. The work produced can often be published as one or more journal papers, and in some cases this could be an alternative to a thesis.

Those who are doing doctoral research can be called a range of different things, by different people or organisations, including:

- Doctoral student

- Doctoral research student

- Research student

- Postgraduate researcher

- Doctoral candidate

Types of doctoral qualification

In the UK, those doing a doctorate (‘doctoral candidates’) are registered as students, which is different from the situation in some other countries. Many undertake their doctorate on a full-time basis based at a university, but others do it part time alongside a full-time or part-time job. Doctorates can be based in a university, a research institute or in another setting such as industry, but there will always be a university involved which ultimately awards the qualification.

Very broadly, there are two main types of doctorate:

-

Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, or occasionally DPhil) which is the most common and familiar form of doctoral qualification. This is undertaken while registered at a university or other higher education institution. Assessment is usually through examination of a written thesis at the end of the doctorate, and a ‘viva’ which is an oral exam.

-

Professional or practice-based doctorates (EngD, EdD, DBA, DPsych etc) are different as they are taken by working people and normally located in that work environment and/or related to their area of practice; for example, research into nutrition for somebody working as a professional nutritionist. These are relatively rare in STEM subjects. In some cases this is the entry qualification for a profession linked to a licence to practice, such as psychology.

Funding

The issue of funding for a doctorate (to cover university fees and living expenses) is really important. Universities charge fees to cover the cost of supervising a doctorate and provide facilities such as a lab or office space. Given that a doctorate will often take 3-4 years if studied full time (longer if part time) it is also crucial that living expenses are covered.

Funding can come from one or more sources, including the UK Research Councils, certain charities or other research bodies/agencies, sometimes from industry, or for international students from an overseas government or the EU. Another major source is the university itself. Doctorates can also be self-funded by the doctoral researcher themselves (or by their employer if they are working). Quite often, funding will be partial and there will be some extent of self-funding.

The position varies widely for different disciplines. In STEM, most doctorates are funded (with perhaps only one in three self-funded). In the arts and humanities, far more are self-funded. The relevant Research Councils are the largest funders of UK students, for example the Engineering & Physical Science Research Council funds one in four UK doctorates in those subject areas.

If a candidate is considering self-funding, they will need to be very confident that this large investment of money and time will be rewarded in the long-term, potentially through their subsequent career. In recent years, a loan scheme has been introduced by the UK government to help those considering self-funding or those unable to achieve full funding from elsewhere.

Many universities will help by offering graduate teaching assistant posts to those studying a doctorate – this is paid part-time work in the university in parallel with the doctorate.

Full funding should cover the university fees (at least £5000 per year) and also pay the candidate a ‘stipend’ – essentially a tax-free salary. The Research Councils currently pay a stipend of around £18,000 per year for three or four years, although this may be higher in London. If there is an additional funder, it is possible that more could be paid. However, some funding bodies only pay the university fees and offer a lower contribution to living expenses; each funding body will have its own rules.

Funded doctoral programmes

The type of doctoral programme varies with the funder. Currently, most of the funding from Research Councils is through ‘studentships’ within collaborative doctoral programmes. A ‘PhD studentship’ refers to a funded doctorate opportunity for which you could apply within one of these programmes (see 'Requirements and how to apply' below). There are services available that list doctoral funding sources/opportunities, and give more guidance on funding, for example:

Collaborative doctoral training is a generic term that covers doctorates where the student undertakes their research at a university or research organisation that is in partnership with other universities, research organisations or industry. A key aspect is that the programme includes training and opportunities to develop a wider range of skills (both academic, and for future careers).

Examples of these Research Council programmes include Doctoral Training Partnerships. Centres for Doctoral Training, Collaborative Doctoral Partnerships/Awards and CASE studentships (which are with industry). Find studentships and doctoral training | UKRI

However, many other doctorates are studied outside these specific types of programme, although those students may also be able to take advantage of some of the same training and development opportunities. The additional opportunities offered can be valuable for the research itself, but are especially so for the candidate’s future career, whether that is within or outside of the academic environment.

Who does doctoral research?

At any one time, there are about 80,000 people studying doctorates in STEM subjects in the UK (compared with about 2.5 million higher education students in total, across all subjects and levels). Around 18,000 people complete a doctorate in STEM each year. Across all subject areas, the breakdown is roughly:

- 9%

- Biological sciences

- 22%

- Biomedical sciences

- 32%

- Physical sciences, engineering, computing

- 14%

- Social sciences

- 13%

- Arts and humanities

The profile of doctoral candidates varies with the discipline. In larger universities especially, there will be a large number of international doctoral students, because the UK has a strong reputation for doctoral research. In STEM subjects, many students will be in their twenties and have come straight from a first degree or Master’s, but there will also be mature students with other career experiences. In the social sciences, far more will be mid-career, studying after prior employment or alongside their job.

Traditionally, doctorate students from poorer socio-economic background and from certain ethnic minority backgrounds have been under-represented. Currently there are several initiatives trying to turn this around, including In2research, a programme that involves mentoring and paid research placements. Many of these initiatives focus on encouraging more Black students to undertake doctoral study.

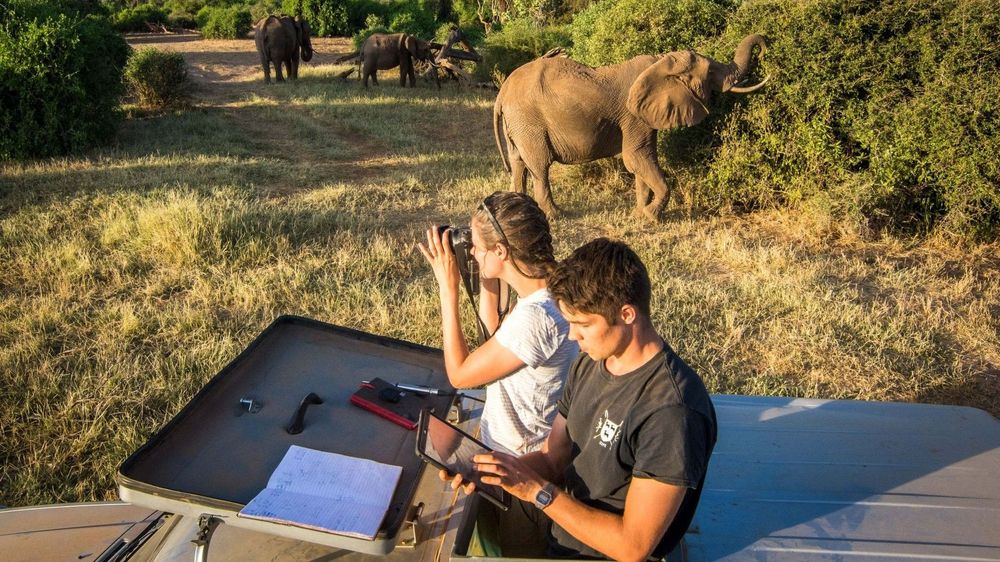

In STEM, many doctoral students will work in a team with other researchers, and/or often spend time together in a lab. In more theoretical areas, and subjects like the humanities, they may find they work far more independently, drawing on the expertise of others as and when the need arises. Many structured doctoral programmes are trying to increase the collaborative aspect of doctoral study.

A great deal has been written about experiences during a doctorate, good and bad, and anybody considering a doctorate should familiarise themselves with at least some of this – it is easy to find through a search like “what it is like doing a PhD”

Requirements and how to apply

Requirements for doctoral opportunities will vary with the programme/funder and the specific university. A good first degree in a relevant subject (with a First Class or 2:1 grade) will be required. Increasingly, a Master’s degree may be a requirement. For some students without a prior Master’s degree, some doctoral programmes may offer a first year of Master’s-level study (for an Master of Research degree) followed by transfer to three years of doctoral study (sometimes known as a 1+3 structure). This is sometimes known as the ‘New route PhD’

What is common for all candidates however, is that they need to be highly motivated by their research topic and to want to make that ‘original contribution to knowledge’.

The application process in the UK is very different from the process of applying for an undergraduate degree, not least because there is no centralised application system. The application method varies according to the higher education institution and the type of programme, but there are broadly two main patterns:

-

Applying for a funded programme. A university will have a range of specific doctoral project opportunities (often called studentships) for which it has funding, and you can apply for one of these, usually in competition with others. These are advertised through sources such as those mentioned above, as well as the university’s website or programme website. Funding from the Research Councils and other major funders tends to be routed this way, via fully-funded studentships.

-

Less commonly in STEM, there is a ‘yet-to-be-funded’ option. This is a two-stage process, where first you apply to a higher education institution – potentially with an idea for what you want to research – and, if they accept you as a potential doctoral candidate, they (and/or you) then seek the funding afterwards. Unsurprisingly, this route may take longer and is more complex than applying for a funded studentship.

Career prospects

Many people assume that a doctorate is the gateway to an academic or research career. However, far more people do doctorates than there are opportunities to enter academic careers. It is therefore important to understand the potential value of a doctorate for a variety of future career paths.

-

For an academic career in a STEM subject, a doctorate is in most cases essential, but it will not guarantee progression to a job – there is simply too much competition.

-

A doctorate could be required or will be valued for jobs which involve doing research, such as in the pharmaceutical industry or working in research and development.

-

It might be valued in other working contexts, such as working for government, a charity on science policy, or in scientific publishing or communications.

-

Certain types of doctoral study are highly valued in certain niches – for example investment banks employ mathematically skilled people to undertake quantitative research and modelling of financial markets.

-

Beyond these research-focused organisations that do or use research, the majority of other employers may not understand or value a doctoral qualification and its associated experience much or at all – so you will likely have to compete against applicants with undergraduate degrees.

A key statistic is that less than half of those with a recent UK doctorate degree work in a university. As this table shows, depending on the subject area, 35-50% progress to a job in higher education, of which the majority have a role which is research focused. Between one in five and one in ten work in research outside higher education. The high proportion of biomedical science doctoral graduates entering ‘other common occupations’ includes those working in medical and healthcare settings.

| Biol Sci % | Biomed Sci % | Phys Sci & Engineering % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher Education Research | 37.1 | 24.4 | 32.4 |

| Higher Education Teaching/lecturing | 9.4 | 10.1 | 7.8 |

| Higher Education (other roles) | 2.7 | 5.1 | 2.2 |

| Research outside Higher Education | 19.9 | 9.7 | 12.9 |

| Other teaching | 2.5 | 0.8 | 1.9 |

| Other common doctoral occupations | 14.7 | 43.7 | 32.2 |

| Other | 13.5 | 6.2 | 10.4 |

Occupations of 2018/19 doctoral graduates in employment or self-employment in the UK (all student domiciles). CRAC analysis of HESA Graduate Outcomes data.